When and why was Santa Claus invented in the U.S.A.?

John Pintard was drawn to personal, family, community, and national “ceremonies, rituals, and traditional practices.” When he could not find them, he invented them. Pintard founded the New York Historical Society in 1804 and “played a role in the establishment of Washington’s birthday, the Fourth of July, and even Columbus Day as national holidays.” In 1809 Washington Irving, a fellow member of the historical society, published a satirical book written as “history of New Amsterdam in old Dutch times.” The book mentioned St. Nicholas with his wagon and pipe. (Stephen Nissenbaum, The Battle for Christmas, 55, 64)

|

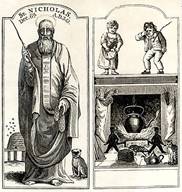

In 1810 Pintard published “a picture of St. Nicholas bringing gifts to children” on St. Nicholas’ Day (Dec. 6). The picture depicted St. Nicholas as a Catholic bishop with a halo and a scepter who came to reward and to punish. In 1819 Irving published a book that included five Christmas stories of different social classes joined in harmony the customs and games of former times. Irving invented the old customs and games described in the stories. This type of Christmas was hard to imagine and impossible for Pintard to reproduce. (ibid., 56–58, 72) (Click on picture to enlarge.) |

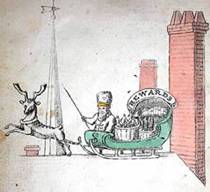

In an anonymous 1821 poem, St. Nicholas or “Sante Claus” came for the first time on Christmas eve in a sleigh pulled by one reindeer. He was still a bishop who rewarded and punished as one would expect on Judgment Day. (ibid., 72–3) We still see this idea in the song that says “You’d better watch out … Santa Claus … knows if you’ve been bad or good.” (Click on picture to enlarge.) |

|

In 1822 Clement Moore, a Hebrew professor, wrote “A Visit from St. Nicholas” that we know as “The Night Before Christmas.” There was “nothing to dread.” St. Nicholas is cheerful, laughs, and leaves only presents and goodwill. He was not a bishop with scepter or robe. He is described as a worker who acts like a nobleman. The “clatter” outside was not drunken wassailers but Santa coming in a sleigh pulled by eight reindeer. As he left he exclaims “Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good-night!” (ibid., 78–88) (Click on picture to enlarge.) |

The poem described a simple way for a family to celebrate Christmas with gifts to their own children. Instead of rowdy, threatening, and drinking wassailers demanding gifts as they roamed the streets, the poem moved gift giving into the home where there was “nothing to dread.” Over the next several years, “the rowdier ways of celebrating Christmas had [not] disappeared, or even … diminished, but … a new kind of holiday celebration, domestic and child-centered, had been fashioned and was now being claimed as the ‘real’ Christmas. The rest of it—public drunkenness and threats or acts of violence, ‘rough music’—had been redefined as crime, ‘making night hideous.’” From 1827 to 1832 Pintard went to church on Christmas day and developed a family tradition in which “St. Claas … came during the night, with most elegant toys, bon bons, oranges, etc.” for his grandchildren (Nissenbaum, 99, 61–62). In the 1820s, Santa Claus was referred to as Saint Nicholas, St. Nicholas, St. Claas, Santeclaus, and Sancte Claus. By the 1850s he is commonly referred to as Santa Claus, an Americanization of his Dutch name, Sinterklaas or Sante Klaas. In Latin based languages like Spanish, Santa means holy or holy one (saint) as we see in Santa Biblia (Holy Bible) and Santa Maria (Saint Mary).

In Oct. 5, 1843 Charles Dickens spoke at a charitable institution on the need to educate the poor. After an enthusiastic response, he walked the streets pondering ways to get good people to help the poor and got the idea for a story. He returned to London and began writing night and day. On Dec. 17 A Christmas Carol was published. By Christmas the first edition was sold out. (Jack Elliot, Inventing Christmas, 108–112) This classic story of Ebenezer Scrooge helped restore the Christmas spirit and revive family Christmas traditions. About that time, Christmas gifts to family and friends took the form of “presents” and gifts to the needy took the form of “charity.” (Nissenbaum, 227)

Before 1820, Christmas was a time of public ‘eat drink and be merry’ celebrations. Beginning about 1820, the foundation for private family giving traditions began. Coincidently, the restoration of the gospel began at the same time. As I compare the two types of Christmas traditions, I wonder how Moroni’s comment on judging applies.

“The devil … inviteth and enticeth to sin, and to do that which is evil continually. But behold, that which is of God inviteth and enticeth to do good continually; wherefore, every thing which inviteth and enticeth to do good, and to love God, and to serve him, is inspired of God.” (Moroni 7:12–13)